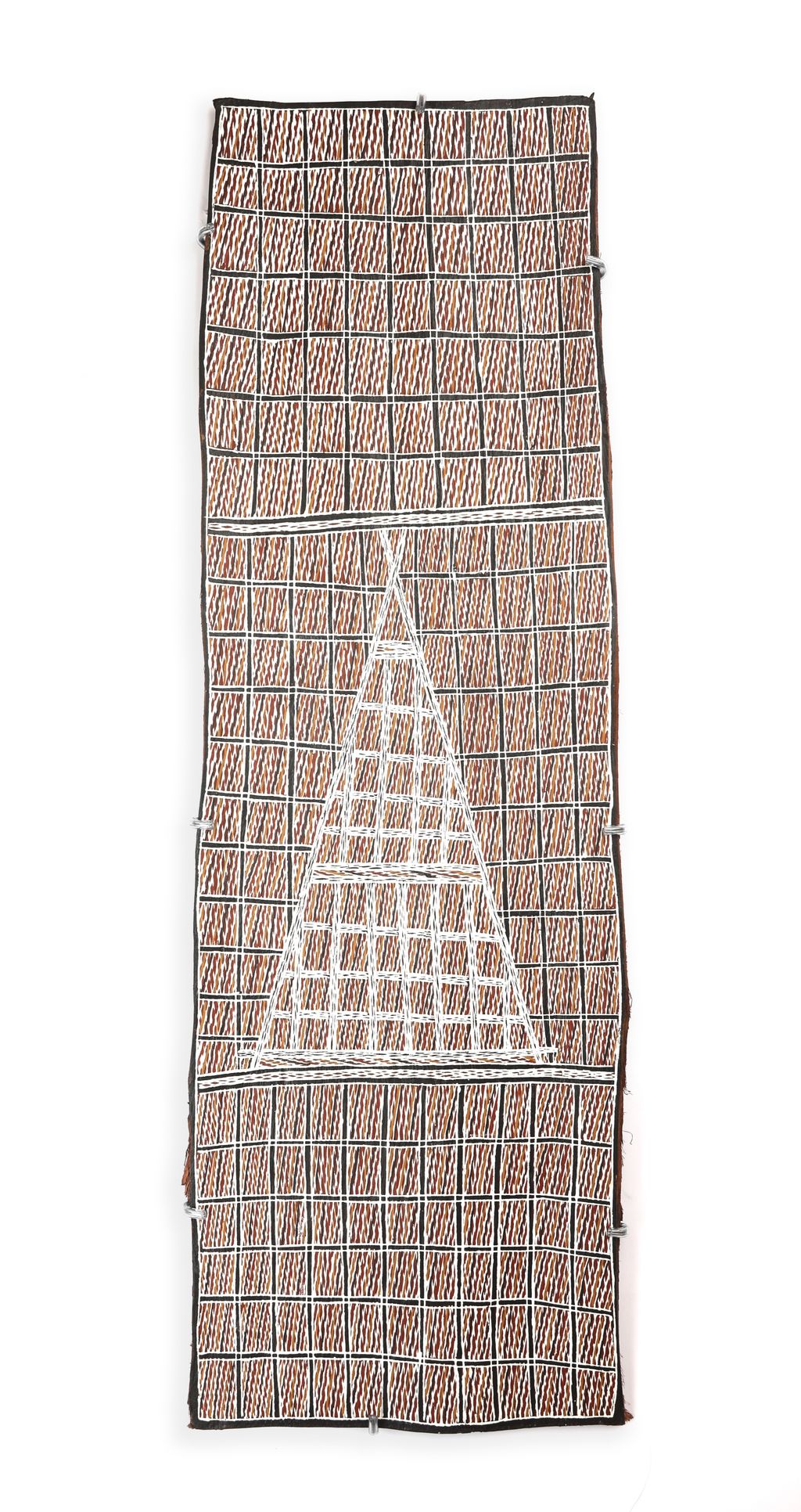

Description

rerrkirrwana munungurr

Earth pigments on Stringybark

78 x 26cm

Year: 2024

ID: 2196-24

Djapu

The cross hatching grid pattern is the sacred design for the fresh waters of the Djapu clan at their homeland Waṉḏawuy now an outstation about 150 kilometres south of Yirrkala and inland from Blue Mud Bay.

This Djapu clan outstation (and spiritual residence for Ancestral Beings Mäna the Shark and Bol’ŋu the Thunderman) is surrounded by permanent freshwater. Rains inspired by the actions of Bol’ŋu feed the rivers and fill the billabongs. Catfish and mussels, freshwater crayfish and others feed the Yolŋu and wild life. The waters are home for the shark Mäna.

The grid refers to the landscape of Waṉḏawuy – a network of billabongs surrounded by ridges and high banks. Its structure also having reference at one level to woven fish traps. Ancestral Hunters set a trap here to snare the Shark but to no avail. These Yolŋu people are called Bärngbarng and Monu’a who came to cut the trees named Gu’uwu, Gathurrmakarr, Nyenyi, Rulwirrika and Gananyarra – all Dhuwa trees. They used straight young trees. And cut them with their axes called Gayma’arri, Bitjutju.

Areas of the river are staked by the Yolŋu and branches interwoven through them. Then the water is polluted by a particular pulped bark that anaesthetises the Gaṉŋal that hobble to the surface. With nets constructed similarly to the the beak of Galumay the Pelican, the Yolŋu wade through the waters scooping up the fish. It has been fished since Ancestral times. Gaṉŋal the catfish, totem for the Djapu is ceremonially sung as is Galumay the pelican. Both these species frequent the waters of Waṉḏawuy.

Mäna the Ancestral Shark in its epic travels comes through this way. These ancestors try to trap Mäna in the freshwater by means of these traps in the waterways. They fail. The powers and physical strength of the Shark overcome the efforts of mere mortals. Mäna’s ire and thrashing tail smash the trap and muddy the water. They witness however the strength of Mäna and sing his actions, the thrashing of his tail for one, the muddying or contamination of the water.

The grid lines having reference to the trap, the cross hatched squares referring to differing states of the freshwater – the source of Djapu soul. At ceremony appropriate participants for mortuary rites enter the shelter (woven together like the unsuccessful trap) where the deceased has been lying in state. Sacred spears tipped with stingray barbs, manifestations of Mäna’s teeth, stand up alongside the shelter. The sacred song cycles of Mäna in the water at Waṉḏawuy are intoned with music from the Yiḏaki (Didjeridu) and Bilma (clapsticks). At the prescribed time at the conclusion of ceremony the dancers crash through the deceased’s shelter imitating the actions of Mäna at the trap. This action has reference to the release of the deceased’s soul, back to the sacred waters of Waṉḏawuy to be reunited with its ancestors awaiting rebirth.

Waṉḏawuy literally means place of the Sharks head where in the larger context of the song cycles of Mäna’s journey his head came to rest after being butchered and distributed through the land. The artist is ‘playing’ with the sacred design to create a completely new pattern suggested by the swirling combinations of different elements of this water.

Djukurr, the shark’s liver represents the djukurr or yothu (child) of Djapu women who are of necessity married to men from the opposite Yirritja moiety. The children of these unions are born with their father’s kinship identity. Djapu people stress the inherent identity of the child as ‘coming from the shark’. Put crudely ‘you can take the liver out of the shark but you can’t take the shark out of the liver’. A female ‘shark’ sees her own Yirritja children as having the essence of “Djapu-ness” within them. This is perhaps understood more concretely by Yolŋu who eat the raw livers of baby sharks and stingrays as a mixed with their cooked and clean white flesh as a delicacy similar to salmon pate.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.